The Year Ahead …..(A Creative Reset)

A closing chapter on food, identity, and the stories we choose to call facts.

Trio of Tacos. Recipe created for The Raw Alchemist L2 (Alchemy Academy Bali, 2025)

When food stops nourishing bodies and starts organizing power.

I started this newsletter (blog) in April 2025 with a very practical intention: to create a communication space where I could talk about my work, slowly introduce my services and products, and—more importantly—find a way of communicating that felt coherent with who I am.

I’ve never been a social media person. Or at least, not someone who feels comfortable constantly showing, selling, or performing. But I’ve been around for a long time—through different shapes, projects, and roles. Age gives you that: perspective. You’ve seen systems shift, trends recycle, masks evolve.

Last year, however, something changed. I felt the need to stop waiting and start doing something. Writing has always been that place for me. A place to think, to slow down, to understand. I wanted to learn how to communicate more effectively without losing my sense—especially now, when everything feels the same: the voices, the faces, the clothes, the images, the videos.

This text wasn’t even meant to be a newsletter.

It started as a blog post for The Culinary Journal. What you’re reading now—I honestly don’t know what it is yet. A reduced version? A lighter cut? Half of a longer piece? I’m letting it be what it needs to be.

What I do know is that today marks the end of the first chapter of this content journey.

From February onward, I’ll be writing from a different place, using another pair of glasses. Thanks to a tool shared with me by my colleague Pamela—The 3 Content Pillars—I’ve shaped a new framework for the next year.

I wanted to close this first cycle in a way that felt coherent. I began with My Culinary Journey, using the Hero’s Journey as a narrative structure, and it feels right to end it consciously before moving on. I love frameworks. I love building them and playing with them—even knowing they might fail, or be terrible, or fall apart.

That’s how stories work. And like any good story, mine also started with disruption.

“Escabeche” Carrots (Basque Culinary Center, 2025, San Sebastián)

When the body collapses

Between February and March last year, my body collapsed.

One immune issue followed another. Then came a series of secondary challenges.

At some point, I did a very simple—and very brutal—exercise. I made columns.

One column per condition.

One list per diagnosis.

And under each, I wrote what I was not allowed to eat in order to heal—not only with medication, but through food.

The result was shocking.

What had been my way of eating for nearly twenty years—my identity, my values, my work—suddenly appeared as part of the problem. I spent my savings moving from one specialist to another. From body to mind. From conventional medicine to deeply alternative approaches.

What I got in return was not clarity, but more questions.I need to understand things deeply. I don’t retain information easily—understanding is how I survive. And when I looked at those columns, what I was “allowed” to eat was far removed from:

Who I am as a person—my values, beliefs, identity.

Who I am professionally—not just what I do, but how and why I do it.

I was told I needed to move away from a plant-based diet and reintroduce animal protein as a key part of my recovery. (I’m not looking for solutions here. I spent a whole year trying to understand what was happening.)

Food—the thing that had structured my life, my thinking, my work—became a source of pain. Introducing something I had consciously removed twenty years ago felt like losing a part of myself.

I saw many friends and colleagues going through similar transitions, each for their own reasons. But when your entire way of living, eating, and thinking is so tightly bound to food, change doesn’t feel neutral. It feels personal.

Conflicting messages came from everywhere. From experts. From social media. From my own body. I didn’t recognize myself in this new landscape.

I spent a year limiting myself. Trying to be honest. Trying to give my body what it needed—even when I didn’t fully understand what that was. Because advice, when you ask for it, is often just someone else translating their beliefs, their experience, their truth—rarely your physical, emotional, or ethical reality.

The banana effect

And then, last week, I saw it again: the USDA Food Pyramid.

Along with it came noise. Opinions. Celebration. Outrage. Victory speeches. Especially from those relieved to see animal protein and fat “finally” restored to their rightful place.

And suddenly, I was back in the same questions I’ve been sitting with all year.

Why does food always turn into a battle?

Why does there always have to be a winner?

Circumstances matter. Bodies matter. Context matters.

When I saw the image, my eyes went straight to one detail: the banana.

Why was it placed there?

So far from the other fruits?

Why relegated to the tip—now the base—of the pyramid?

I’m from the Canary Islands. Bananas are not just food for us. They’re cultural, political, territorial, and economic symbols. Who decides this hierarchy? Who decides this narrative?

That question led me to look at the entire image—and the confusion only grew. Who can actually understand what is being recommended here? And why should I, as a Spanish person, feel influenced by guidelines that have little to do with my culture or my way of eating?

So I did what I always do: I read the report. Slowly. Carefully. Trying to understand not just what was in front of me—but what was behind it.

I’m not here to debate nutrition facts.

I’m already confused enough by my own situation.

Instead, I choose to see this pyramid as what it truly is: a cultural artifact. And I want to invite you to look at it through two lenses—two lenses I consider stubbornly real:

a designer’s lens

a climate lens

When design fails to guide

Nutrition “facts,” for me, are rarely facts. Everyone speaks their truth. Everyone wants to win. I’m not interested in winning—I’m interested in healing. But healing from another place: one that is more honest with myself, with the how and the why, not only with the what.

I’m still eating mostly plants. Sometimes a few eggs (rarely). Goat kefir, when I tolerate it. I’ve tried—really tried—to move in another direction. I’ve put myself there. Fish, especially. And yet, I'm often still in the same place. Just plants.

At times, I feel like Louis de Pointe du Lac in Interview with the Vampire—trying to preserve my humanity while caught in a constant internal struggle between the soul’s ethics and the body’s maintenance. Between what I believe and what my system can actually process.

What has become very clear to me is that today’s so-called “nutritional facts” are deeply dependent on personal context: underlying conditions, life stage, stress, history, environment. Singular bodies. Singular stories. It would be revolutionary to truly include those layers—but here we enter thin territory.

Because beneath nutrition lies another question. A quieter, more uncomfortable one:

What do we want—as humans?

And what do we want—as animals?

There is a fragile layer between personal desire and collective purpose. Between instinct and choice. Between what is wild and what has been domesticated in us. And the moment we touch that layer, everything turns into a battle again.

You see?

Always a battle.

And when everything starts to feel like a fight—when the signals are red flags and everything you “know” falls apart—reading other people’s opinions can feel like relief. Not because they’re right, but because you’re no longer alone in the confusion.

Projects Table. The Raw Alchemist L1 (Alchemy Academy, 2025, Bali)

A designer’s lens

Coming back to the banana effect, there are a few things that become particularly revealing when we look at this pyramid as a cultural artifact rather than a nutritional guide.

In a design critique published by STAT News, the pyramid is described as a “resurrected symbol”—reused as the central visual metaphor for how Americans should eat. That phrase alone says a lot. Symbols don’t just inform; they shape hierarchy and values.

Visually, the critique argues, it reflects an outdated way of thinking about communication—more like emoji-style clip art from a 1950s health pamphlet than a contemporary public health tool. And when a health graphic needs to be explained, something fundamental has already failed.

The structure suggests RANK and PRIORITY, not BALANCE. The abundance of icons muddies the message and increases ambiguity—and here, ambiguity matters. Health graphics are not decorative. They are pedagogical tools. Their job is to communicate actionable guidance. On that level, this image struggles.

Even the slogan “Eat Real Food” collapses under scrutiny. What is “real” is neither defined nor clearly portrayed. The image leaves viewers projecting their own assumptions onto the word real—and this is precisely where my beloved banana enters the scene. What hierarchy is being implied? What value judgment is quietly embedded?

Salsify and Hazelnuts (Basque Culinary Center, 2025, San Sebastián)

Why images are never innocent

This brought me back to a question we were taught to ask in school:

Why do we use images to illustrate a document?

Roland Barthes wrote about this in Rhetoric of the Image. For him, images carry three layers of meaning:

The linguistic message: the verbal text attached to the image.(“Eat Real Food”—a phrase meant to anchor meaning, but here failing to do so.)

Denotation: what is literally shown.

(An inverted pyramid. Stacked categories. Discrete food icons. A clear top–bottom hierarchy. Even at this level, the image is not neutral. A pyramid—upright or inverted—demands reading order. It already implies that some foods matter more than others)

Connotation: the cultural, symbolic, and ideological meanings beneath the surface.

(It’s in this third layer that things become uncomfortable—and interesting. I’ll leave that layer open for you. Not to avoid responsibility, but to avoid turning this into another battle of beliefs. Instead, I invite you to think.)

When food starts organizing power

The result, when the image fails, is predictable:

Confusion instead of guidance.

Projection instead of understanding.

Debate instead of action.

A health image should answer: What should I do?

This one asks instead: What do you believe?

By presenting itself as neutral, universal, and self-evident, the image quietly embeds hierarchy, ideology, and cultural bias. And when food images do that, they stop nourishing bodies and start organizing power.

This is where I want to pause again—at that thin, uncomfortable layer between personal desire and collective purpose.

Because food guidelines—and the images that carry them—are not only nutritional. They shape production systems. They influence what is grown, what is subsidized, what is normalized. And those systems have consequences far beyond the individual plate.

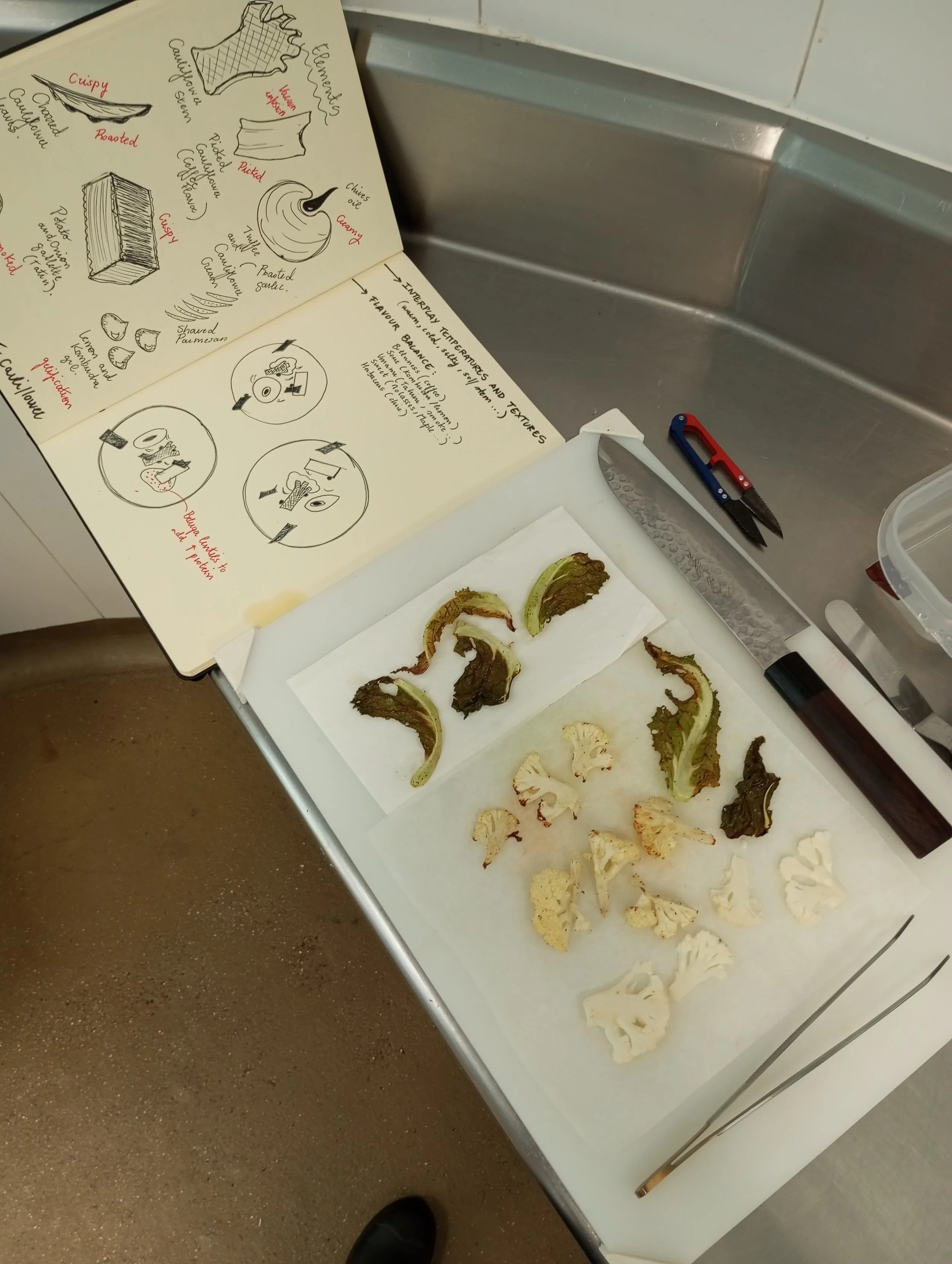

Surprise Box – cauliflower, potato, almonds (Basque Culinary Center, 2025, San Sebastián)

Climate, desire, and restraint

While writing this, I had the radio on in the background. I wasn’t really listening until I heard a book recommendation that suddenly clicked into place: Ciencia ficción capitalista by Michel Nieva.

One chapter title alone felt disturbingly relevant: “Climate Change: The Great Pride of the White Man.” Nieva explores how apocalyptic narratives are often framed as fantasies of control—where a certain figure, often the macho businessman, imagines himself as the one capable of fixing the end of the world.

He connects this to cultural performances of masculinity: excess, domination, spectacle. Even something as banal as celebrating meat consumption—burning as much charcoal as possible, grilling as if there were no limits—becomes a symbolic act. A performance of power.

I can’t get the image out of my head: groups of half-naked men, proud of their grills, their meat, their fire—as if there were no other option. As if restraint were weakness. As if abundance were proof of worth.

I’m trying here to avoid personal bias. This is not about morality.

This is about facts.

From a climate perspective, facts are stubborn:

Methane matters as much as carbon.

High-methane food systems—particularly industrial animal agriculture—are a major climate concern.

Dietary recommendations that normalize or increase reliance on those systems are therefore not neutral. They are collective decisions with planetary consequences.

This is where desire becomes political, whether we want it or not.

Surprise Box – cauliflower, potato, almonds (Basque Culinary Center, 2025, San Sebastián)

Long before climate science, philosophers like Pythagoras and Epictetus were already wrestling with this tension. True freedom, they argued, is not doing whatever we want—but being able to govern ourselves.

From this angle, climate responsibility is not about purity or sacrifice. It’s about maturity. About understanding that not every desire needs to be amplified into a system.

We don’t need to reopen—again—the scientific debate on the benefits of plant-rich diets. That evidence already exists.

What matters here is something else:

How images, guidelines, and cultural narratives quietly teach us what kind of desire is acceptable, and which futures are imaginable.

And whether we are willing to imagine something beyond them.

Dewa Ayu's Ginger Flower Class, "The Connection Between Plants and Our Environment" (Alchemy Academy, 2025, Bali)

A small detour: the animal behind the icon

One more thing about the emoji logic in this graphic (and many more): when it refers to animal products, it usually shows what people eat (a steak, a cooked chicken, a slice of cheese), rather than the animal itself: a whole cow, a whole chicken. It's a strange visual choice. It flattens reality.

And it made me think about something else I came across this week: Veronika.

Veronika is a cow in Austria who was observed using objects—sticks and even a broom—to scratch parts of her body she couldn’t easily reach. Researchers documented her choosing different parts of the tool depending on sensitivity: bristles for some areas, the handle for more delicate ones.

This is not sentimentality. It's an observation.

Cows itch, just like us. They solve problems, when their environment allows it.

Whether you like it or not, that’s a fact too.

Borrowing from one of the pandemic’s most haunting memes, inspired by Soylent Green (1973):

“People were always rotten.

But the world was beautiful.”

Do you believe it?

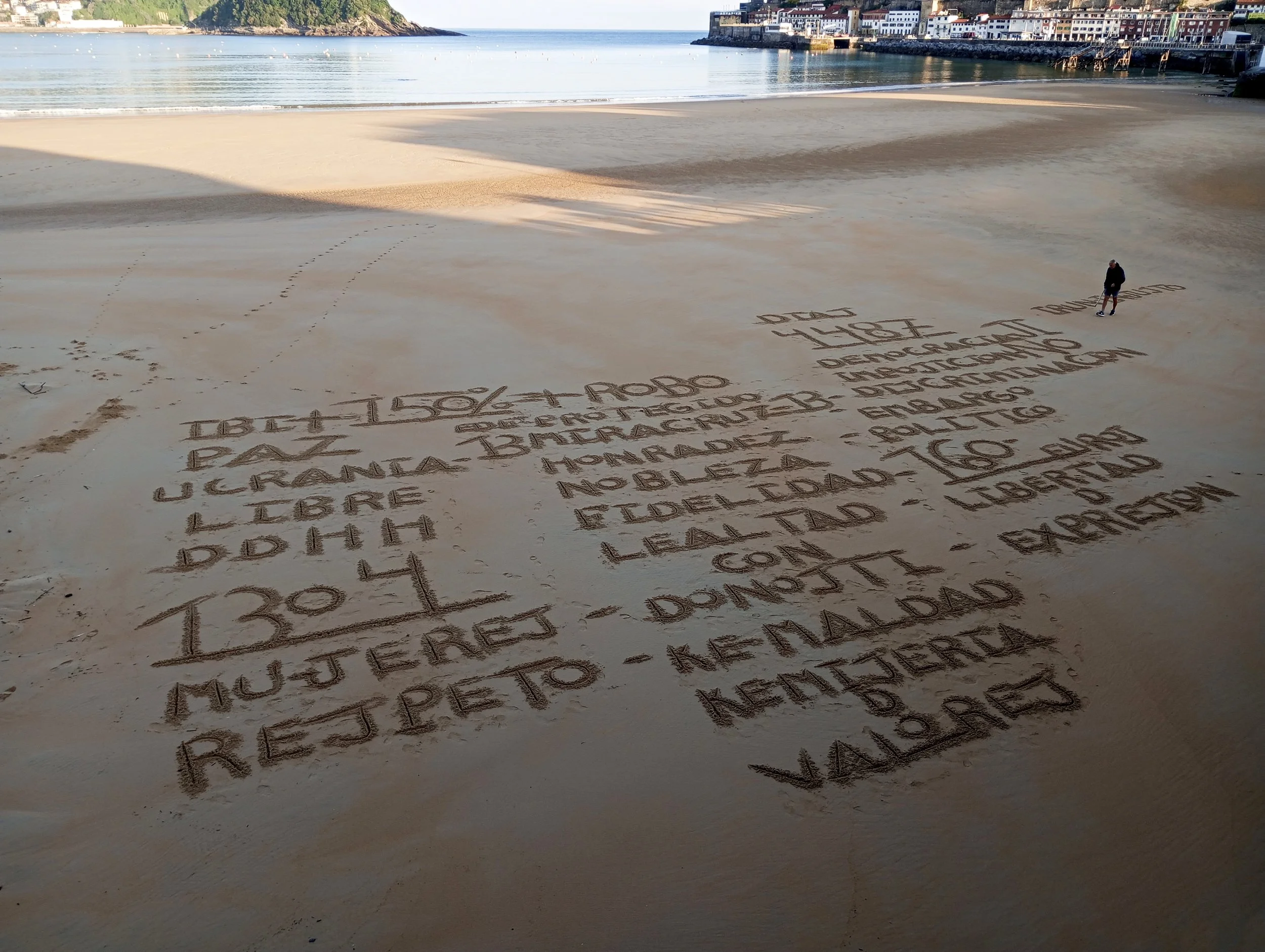

Manifesto on "La Concha" beach. Written every day at low tide (San Sebastián, 2025)

Support My Work

If this helped you, consider sharing it with a friend, subscribing to my newsletter, or buying me a coffee. This space is a labor of love—and your support helps me keep building it.